World War II (abbreviated WWII), or the Second World War, was a worldwide military conflict which lasted from 1939 to 1945. World War II was the amalgamation of two conflicts, one starting in Asia, 1937, as the Second Sino-Japanese War and the other beginning in Europe, 1939, with the invasion of Poland.

This global conflict split a majority of the world's nations into two opposing camps: the Allies and the Axis. Spanning much of the globe, World War II resulted in the deaths of over 60 million people, making it the deadliest conflict in human history.[1]

World War II was the most widespread war in history, and countries involved mobilized more than 100 million military personnel. Total war erased the distinction between civil and military resources and saw the complete activation of a nation's economic, industrial, and scientific capabilities for the purposes of the war effort; nearly two-thirds of those killed in the war were civilians. For example, nearly 11 million of the civilian casualties were victims of the Holocaust, which was largely conducted in Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union.

The conflict ended in an Allied victory. As a result, the United States and Soviet Union emerged as the world's two leading superpowers, setting the stage for the Cold War for the next 45 years. Self determination gave rise to decolonization/independence movements in Asia and Africa, while Europe itself began traveling the road leading to integration.

Course of the war

Overview

- See also: Timeline of World War II

In September, 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria under false pretexts and captured it from the Chinese. In 1937, Japan again attacked China, starting the Second Sino-Japanese War.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler of the Nazi Party became leader of Germany. Under the Nazis, Germany began to rearm and to pursue a new nationalist foreign policy. By 1937, Hitler also began demanding the cession of territories which had historically been part of Germany, like Rhineland and Gdansk.

In Europe, Germany, and to a lesser extent Italy, asserted increasingly hostile and aggressive foreign policies and demands, which the United Kingdom and France initially attempted to diffuse primarily through diplomacy and appeasement.

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and war in Europe followed. The United Kingdom and France declared war. The French and British did not declare war at first, hoping they could presuade Hitler to diplomacy, but Hitler failed to respond. During the winter of 1939/1940 there was little indication of hostilities since neither side was willing to engage the other directly. This period was called the Phoney War.

In 1940, Germany captured Denmark and Norway in the spring, and then in the early summer France and the Low Countries. The United Kingdom was then targeted; the Germans attempted to cut the island off from vitally needed supplies and obtain air superiority in order to make an seaborne invasion possible. This never came to pass, but the Germans continued to attack the British mainland throughout the war, primarily from the air. Unable to engage German forces on the continent, the United Kingdom concentrated on combating German and Italian forces in the Mediterranean Basin. It had limited success however; it failed to prevent the Axis conquest of the Balkans and fought indecisively in the Western Desert Campaign. It had greater success in the Mediterranean Sea, dealing severe damage to the Italian Navy, and dealt Germany's first major defeat by winning the Battle of Britain.

In June 1941, the war expanded dramatically when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, bringing the Soviet Union into alliance with the United Kingdom. The German attack started strong, overrunning great tracts of Soviet territory, but began to stall by the winter.

Since invading Manchuria, Japan had been subjected to increasing economic sanctions by the United States and other Western nations, and was attempting to reduce these sanctions through diplomatic negotiations. In December 1941, however, the war expanded again when Japan, already into its fifth year of war with China, launched near simultaneous attacks against the United States and British assets in Southeast Asia; four days later, Germany declared war on the United States. This brought the United States and Japan into the greater conflict and turned previously separate Asian and European wars into a single global one.

In 1942, though Axis forces continued to make gains, the tide began to turn. Japan suffered its first major defeat against American forces in the Battle of Midway, where 4 of Japan's Aircraft carriers were destroyed. German forces in Africa were being pushed back by Anglo-American forces, and Germany's renewed summer offensive in the Soviet Union had ground to a halt.

In 1943 Germany suffered devastating losses to the Soviets at Stalingrad, and then again at Kursk, the greatest tank battle in military history. Their forces were expelled from Africa, and Allied forces began driving northward up through Sicily and Italy. The Japanese continued to lose ground as the American forces seized island after island in the Pacific Ocean.

In 1944, the outcome of the war was becoming clearly unfavorable for the Axis. Germany became boxed in as the Soviet offensive became a juggernaut in the east, pushing the Germans out of Russia and pressing into Poland and Romania; in the west, the Western Allies invaded mainland Europe, liberating France and the Low Countries and reaching Germany's western borders. While Japan launched a successful major offensive in China, in the Pacific, their navy suffered continued heavy losses as American forces captured airfields within bombing range of Tokyo.

In 1945 the war ended. In Europe, a final German counter-attack in the west failed, while Soviet forces captured Berlin in May, forcing Germany to surrender. In Asia, American forces captured the Japanese islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa while British forces in Southeast Asia managed to expel Japanese forces there. Initially unwilling to surrender, Japan finally capitulated after the Soviet Union invaded Manchukuo and the United States dropped atomic bombs on the mainland of Japan.

European Theatre

Events leading up to the war in Europe

Germany and France had been struggling for dominance in Continental Europe for 80 years and had fought two previous wars, the Franco-Prussian War and World War I. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Communist revolutionary movements began spreading across Europe, briefly taking power in both Budapest and Bavaria; in response, extreme right-wing Fascist and Nationalist groups were born.[2]

In 1922, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and his fascist party took control of the Kingdom of Italy and set the model for German dictator Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party, which, aided by the civil unrest caused by the Great Depression, took power in Germany and eliminated its democratic government, the Weimar Republic. These two leaders began to re-militarize their countries and become increasingly hostile. Mussolini first conquered the African nation of Abyssinia and then seized Albania, with both Italy and Germany actively supporting Francisco Franco's fascist Falange party in the Spanish Civil War against the Second Spanish Republic (which was supported by the Soviet Union). Hitler then broke the Treaty of Versailles by increasing the size of the Germany's military, and re-militarized the Rhineland. He started his own expansion by annexing Austria and sought the same against the German-speaking regions (Sudetenland) of Czechoslovakia.

The British and French governments followed a policy of appeasement in order to avoid military confrontation after the high cost of the First World War. This policy culminated in the Munich Agreement in 1938, which would give the Sudetenland to Germany in exchange for Germany making no further territorial claims in Europe.[3][4] In March 1939, Germany disregarded the agreement and annexed the remainder of Czechoslovakia. Mussolini, following suit, annexed Albania in April.

The failure of the Munich Agreement showed that negotiations with Hitler could not be trusted, and that his aspirations for dominance in Europe went beyond what the United Kingdom and France would tolerate. France and Poland pledged on May 19, 1939, to provide each other with military assistance in the event either was attacked. The following August, the British guaranteed the same.

On August 23, 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact which provided for sales of oil and food from the Soviets to Germany, thus reducing the danger of a British blockade such as the one that had nearly starved Germany in World War I. Also included was a secret agreement that would divide Central Europe into German and Soviet areas of interest, including a provision to partition Poland. Each country agreed to allow the other a free hand in its area of influence, including military occupation.

Germany's war against the Western Allies

Blitzkrieg

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, using the false pretext of a faked "Polish attack" on a German border post. On September 3, the United Kingdom issued an ultimatum to Germany. No reply was received, and Britain, Australia and New Zealand declared war on Germany, followed later that day by France. Soon afterwards, South Africa, Canada and Nepal also declared war on Germany. Immediately, Great Britain began seizing German ships and implementing a blockade.

Despite the French and British treaty obligations and promises to the Polish government, both France and Great Britain were unwilling to launch a full invasion of Germany. The French mobilized slowly and then mounted only a short token offensive in the Saar; neither did the British send land forces in time to support the Poles. Meanwhile, on September 8, the Germans reached Warsaw, having ripped through the Polish defenses. On September 17, the Soviet Union, pursuant to its prior agreement with Germany, invaded Poland from the east. Poland was soon overwhelmed, and the last Polish units surrendered on October 6.

After Poland fell, Germany paused to regroup during the winter while the British and French stayed on the defensive. The period was referred to by journalists as "the Phoney War" because of the inaction on both sides. In Eastern Europe, the Soviets began occupying Baltic states leading to a confrontation with Finland, a conflict which ended with land concessions to the Soviets on March 12, 1940. In early April 1940, both German and Allied forces launched nearly simultaneous operations around Norway over access to Swedish iron ore. It was a short campaign which resulted in complete German control of Denmark and Norway, though at a heavy cost to their surface navy. The fall of Norway led to the Norway Debate in London, which resulted in the resignation of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who was replaced by Winston Churchill.

On May 10, 1940, the Germans invaded France and the Low Countries. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French Army advanced into Flanders and planned to fight a mobile war in the north, while maintaining a static continuous front along the Maginot Line further south. This was foiled by an unexpected German thrust through the Ardennes, splitting the Allies in two. The BEF and French forces, encircled in the north, were evacuated from Dunkirk in Operation Dynamo. France, overwhelmed by the blitzkrieg, was forced to sign an armistice with Germany on June 22, 1940, leading to the direct German occupation of Paris and two-thirds of France, and the establishment of a German puppet state headquartered in southeastern France known as Vichy France.

With only the United Kingdom remaining as an opposing force in Europe, Germany began to prepare Operation Sealion, the invasion of Britain. Most of the British Army's heavy weapons and supplies had been lost at Dunkirk, but the Royal Navy was still stronger than the Kriegsmarine and kept control of the English Channel. The Germans then attempted to gain air superiority by destroying the Royal Air Force (RAF) using the Luftwaffe. The ensuing air war in the late summer of 1940 became known as the Battle of Britain. The Luftwaffe initially targeted RAF Fighter Command aerodromes and radar stations, but Luftwaffe Commander Hermann Göring and Hitler, angered by British bombing raids on German cities, switched their attention towards bombing English cities, an offensive which became known as The Blitz. This diversion of resources allowed the RAF to rebuild their airbases, eventually leading Hitler to give up on his goal of establishing air superiority over the English Channel; this in turn led to the permanent postponing of Operation Sealion.

With Germany and her allies having total control of the continent, the United Kingdom and its allies settled for strategic bombing and special forces operations in mainland Europe. Many of the conquered nations formed governments in exile and military units within the United Kingdom as well as domestic resistance movements. Germany, meanwhile, fortified its position by constructing the Atlantic Wall.

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, a nautical campaign which lasted the duration of the war, started after the German invasion of Poland with the torpedoing of the British liner SS Athenia by a German submarine (U-boat). Having faced raids on shipping during the First World War, the British quickly implemented a convoy solution to protect merchant vessels; they were short of escort ships though, so many merchant ships had to sail without protection. At first, U-boats primarily operated within British waters while the Atlantic Ocean was covered by German surface vessels. The British attempted to counter the U-boat threat by forming anti-submarine hunting groups, which were ultimately ineffective because the U-boats proved too elusive.

With the German conquest of Norway and France by June 1940, U-boats enjoyed decreased resistance. The French Navy was removed as an Allied force, and additional ports in France on the Atlantic Ocean became available to the German Navy (Kriegsmarine), allowing them to increase the range of their vessels. The Royal Navy became severely stretched, having to remain stationed in the English Channel to protect against a German invasion, send forces to the Mediterranean Sea to make up for the loss of the French fleet, and provide escort for merchant vessels. This was somewhat mitigated by the Destroyers for Bases Agreement with the United States Navy in September 1940, in which the British exchanged several of their oversea bases for fifty destroyers which were then used for escort duties. The success of U-boats in this period led to an increase of their production and the development of the wolf pack technique.

The German surface navy, which had suffered substantial losses in the capture of Norway, had mixed results. While there were several successful merchant raids, such as Operation Berlin, they also suffered several losses, such as the battleships Graf Spee and Bismarck. The loss of the Bismarck had deeper ramifications on naval policy though, because as a result Hitler ordered all heavy surface vessels to Norwegian waters[2], shifting them from raiding operations to protection from a potential Allied invasion of Scandinavia. While the Royal Navy also suffered the loss of capital ships, such as the aircraft carrier HMS Courageous, the battleship HMS Royal Oak and the battlecruiser HMS Hood, their larger surface navy was better able to absorb the losses.

In May 1941, the British captured an intact Enigma machine, which greatly assisted in breaking German codes and allowed for plotting convoy routes which evaded U-boat positions. In the summer of 1941, the Soviet Union entered the war on the side of the Allies, but they lost much of their equipment and manufacturing base in the first few weeks following the German invasion. The Western Allies attempted to remedy this by sending Arctic convoys, which faced constant harassment from German forces. In September, many of the U-boats operating in the Atlantic were ordered to the Mediterranean to block British supply routes. When the United States entered the war that December, they did not take precautionary anti-submarine measures; this resulted in shipping losses so great that the Germans referred to it as a second happy time.

In February 1942, several German capital ships that were stationed in the port of Brest, France, managed to comply with Hitler's earlier order and slipped through the English Channel to their home bases in German waters, dealing a significant blow to the Royal Navy's reputation. In June, the Leigh light allowed Allied aircraft to illuminate U-boats that had been detected by the airplanes radar, but this was soon negated by the Germans with Metox, a radar detection system that gave them advance notice of such an aircraft's approach. In American waters, the institution of shore blackouts and an interlocking convoy system resulted in a drop in attacks, and the U-boats shifted their operations back to the mid-Atlantic by August. In December, a strong German surface navy force engaged an Arctic convoy destined for the Soviet Union and failed to destroy a single merchant ship; this resulted in the resignation of Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) Erich Raeder, supreme commander of the Kriegsmarine. He was replaced by Commander of Submarines Karl Dönitz, and all naval building priorities turned to the U-boats.

In January, 1943, the British developed the H2S radar system which was undetectable by Metox. As before, this was followed by a counter-invention on the German side, the Naxos radar detector, which allowed German fighters to hone in on Allied aircraft utilizing the H2S. In the spring, the Battle of the Atlantic began to turn in favour of the Allies with the pivotal point being Black May, a period where the Allies had fewer ships sunk and the Kriegsmarine lost 25% of their active U-boats. That December, the German surface fleet lost their last active battlecruiser in the Battle of North Cape. By this time, the Kriegsmarine was unable to regain the initiative; Allied production, such as the mass-produced Liberty ships, improved antisubmarine warfare tactics, sea route patrols with long range attack aircraft, and ever-improving technology led to increasing U-boat losses and more supplies getting through. This allowed for the massive supply build up in the United Kingdom needed for the eventual invasion of Western Europe in mid-1944.

Mediterranean, Africa, and the Middle East

Control of Southern Europe, the Mediterranean Sea and North Africa was important because the British Empire depended on shipping through the Suez Canal. If the canal fell into Axis hands or if the Royal Navy lost control of the Mediterranean, then transport between the United Kingdom, India, and Australia would have to go around the Cape of Good Hope, an increase of several thousand miles.

Almost immediately after declaring war on France and the United Kingdom in June 1940, Italy initiated the siege of Malta, an island under British control located in the Mediterranean between mainland Italy and its colony in Libya. Minimal resources were initially placed by both sides though, the Italians needing to reserve their strength for other planned invasions and the British not believing they could effectively defend it. As the importance of the campaigns in North Africa increased though, so did that of Malta and the disruptions of Axis supply lines that Allied forces stationed there could provide.

Following the French surrender, the British attacked the French Navy anchored in North Africa in July 1940, out of fear that it might fall into German hands; this contributed to a souring of British-French relations for the next few years. Soon following this action was the Battle of Calabria, the first large conflict between the Royal Navy and the Italian Navy (Regia Marina).

With France no longer a threat, Italy was able to relax its guard on its western possessions in Africa which bordered French territory and focus on the British forces in the east. In August, Italy invaded British Somaliland, located in the Horn of Africa, expelling British forces and creating Italian East Africa. The following month, the Italians then made a small incursion into British-held Egypt, starting the Western Desert Campaign.

The United Kingdom, along with the Free French Forces, a collection of resistance fighters under Charles de Gaulle, then attempted to replace Vichy control over French territories with that of the Free French. In September, 1940, they made a failed attempt to capture French West Africa, though in November, they later succeeded in French Equatorial Africa. Between these attempts, the Italians launched their own offensive from Albania and attacked Greece.

Starting in November of 1940, the British had a string of successful operations against Italian forces. On November 12 they launched the first all-aircraft naval attack against the Italian fleet at Taranto. Then, in December, the British Commander-in-Chief of the Middle East, General Archibald Wavell, launched Operation Compass, expelling Italian forces from Egypt and pushing them all the way west across Libya. Starting in January, 1941, he started another offensive into Italian East Africa, conquering the short-lived state. Italy was also facing problems in the Balkans, where the Greek Army had pushed the Italians out of Greece and were now stalemated in southern Albania.

Alarmed by the Italian setbacks, Hitler authorized reinforcements, and sent German forces to Africa in February. The British also started redeploying their forces, sending soldiers from North Africa to Greece starting in early March; in an effort to secure their transportation lines, the Royal Navy managed to engage the Regia Marina in the Battle of Cape Matapan, doing significant damage to the Italian fleet. The German forces in Africa, led by German General Erwin Rommel, however, launched an offensive against the now depleted British forces near the end of March. During this offense, the British also feared having their oil supply cut due to a Nazi-friendly coup d'état in Iraq in early April. They were further pressed when the Germans invaded Greece and Yugoslavia. By the middle of April, Rommel's forces had pushed the British forces back into Egypt with the exception of the port of Tobruk, which he encircled and besieged. Shortly after, the British responded to the coup in Iraq by invading and occupying the country. By the end of May, German forces had conquered Yugoslavia, mainland Greece and further captured the island of Crete, forcing a withdraw of all British forces from the Balkans.

In June 8, the British and Free French invaded Vichy controlled Syria and Lebanon due to the Vichy allowance of Axis forces to pass through the area and utilize military bases. A week later, Wavell launched Operation Battleaxe, which was intended to be a major offensive in the Western Desert, but resulted in the loss of nearly half of the British tanks in the region. Frustrated by the lack of success, Churchill had Wavell replaced with Claude Auchinleck in early July. In late August, after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the British and the Soviets launched a joint invasion of Iran to secure its oilfields and the Persian Corridor supply route for Soviet use.

There was then a lull in activity. The Soviet-German war had significantly reduced the importance of the Mediterranean theatre to the Germans and the British spent their time building up their forces. On November 18, they launched Operation Crusader, an offensive in the Western Desert which pushed Rommel back to his original starting point at El Agheila in Libya. The British suffered a significant blow in the sea though, losing several ships shortly after the First Battle of Sirte.

With the entry of Japan into the war in December 1941, the British were again forced to withdraw units from the Western Desert, this time transferring them to Burma. Once again Rommel took advantage of the situation, and on January 21, launched an offensive which pushed the British back to Gazala, just west of Tobruk. There was another lull in activity as both sides built up their forces. In May, after the Japanese Indian Ocean raid, the British invaded Vichy controlled Madagascar to prevent the Imperial Japanese Navy from using as launch point for further such attacks. Rommel then launched his own attack in late May, overrunning the British position in the Western Desert and chasing them well into Egypt, being halted at El Alamein. Shortly after, the Royal Navy suffered significant damage getting much needed supplies to Malta.

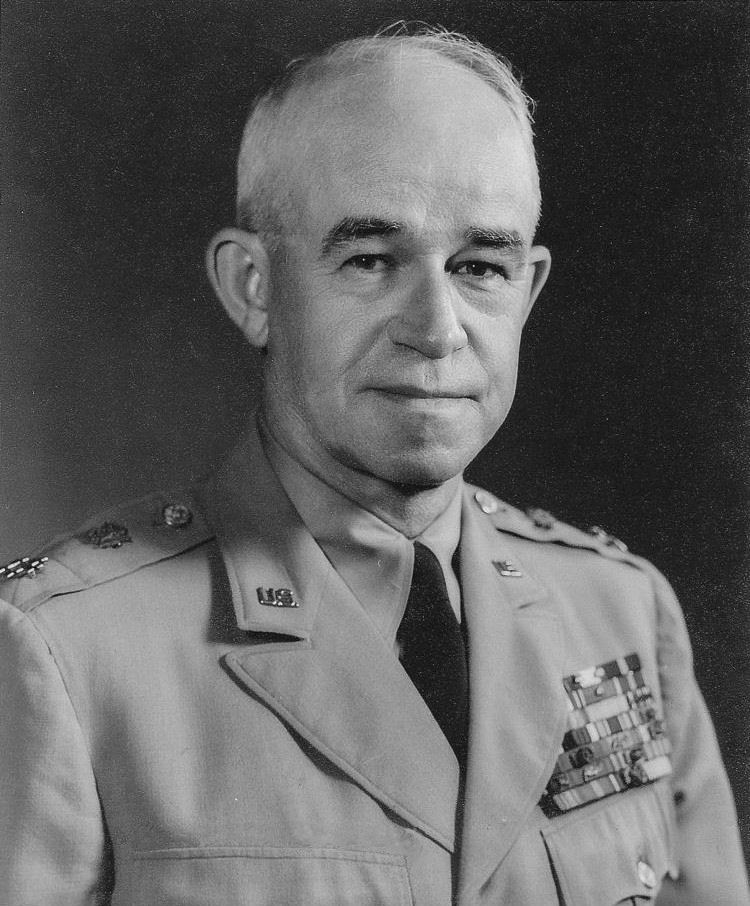

Like Wavell before him, Auchinleck's perceived failures led to his replacement by Churchill, this time by Harold Alexander with Bernard Montgomery taking over the ground forces in Egypt.

In late October, after building up his forces, Montgomery launched his offensive, pushing the Axis forces back and pursuing them across the desert. In November, Anglo-American forces landed in Vichy-controlled Northwest Africa with minimal resistance; in retaliation, the Germans seized the remainder of mainland France, though they failed to capture the remainder of the French Navy. Soon, Rommel's forces were pincered in Tunisia and by May of 1943, were forced to evacuate Africa entirely.

In July, the Italian Campaign began with the Allied invasion of Sicily. The continued series of Italian defeats led to Mussolini being dismissed by the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III and subsequently arrested. His successor, Pietro Badoglio, then began negotiating surrender with the Allies. On September 3 the Allies invaded Italy itself and the Italians signed an armistice. This was made public on September 8, the same day the Allies launched a subsequent invasion of the Italian held Dodecanese islands. Germany had been planning for such an event though, and executed Operation Achse, the seizure of northern and central Italy. A few days later, Mussolini was rescued by German special forces and before the end of September created the Italian Social Republic, a German client state.

From October until mid-1944, the Allies fought through a series of defensive lines and fortifications designed to slow down their progress. On April 25, a little over a year and half after its creation, the Italian Social Republic was overthrown by Italian partisans; Mussolini, his mistress and several of his ministers were captured by the partisans while attempting to flee and executed. Shortly after, one of strongest of the German defensive lines, the Winter Line, was breached nearly simultaneously in May at Monte Cassino by British-led forces and at Anzio by the Americans; though the Allies could have encircled and potentially destroyed the bulk of German forces in Italy, the American forces instead moved towards Rome, capturing the city on June 4.

In August, Allied forces in Italy were divided, with a significant portion sent to southern France to assist in the liberation of Western Europe while the remainder pressed north to engage the remaining German forces, notably at the Gothic Line. Fighting in Italy would continue until early May, 1945, only a few days prior to the general German surrender.

Liberation of Western Europe

| “ | You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world. | ” |

| “ | In the East, the vastness of space will … permit a loss of territory … without suffering a mortal blow to Germany’s chance for survival. Not so in the West! If the enemy here succeeds … consequences of staggering proportions will follow within a short time.[5] | ” |

| — Adolf Hitler |

By the Spring of 1944, the Allied preparations for the invasion of France and the initial stages for the liberation of western Europe (Operation Overlord) were complete. They had assembled around 120 Divisions with over 2 million men, of which 1.3 million were Americans, 600,000 were British and the rest Canadian, Free French and Polish. The invasion, code-named Operation Neptune but commonly referred to as D-Day, was set for June 5th but bad weather postponed the invasion to June 6, 1944.[6] Almost 85–90% of all German troops were deployed on the Eastern Front and only 400,000 Germans in two armies, the German Seventh Army and the newly-created Fifth Panzer Army, were stationed in the area. The Germans had also constructed an elaborate series of fortifications along the coast called the Atlantic Wall, but in many places the Wall was incomplete. The Allied forces under supreme command of Dwight D. Eisenhower had launched an elaborate deception campaign to convince the Germans that the landings would occur in the Calais area which caused the Germans to deploy many of their forces in that sector. Only 50,000 Germans were deployed in the Normandy sector on the day of the invasion.

The invasion began with 17,000 airborne troops being dropped in Normandy to serve as a screening force to prevent the Germans from attacking the beaches. During the early morning, a massive naval flotilla bombarded German defenses on the beaches, but due to lack of visibility most of the shots missed their targets. Additionally, most of the troop transport ships (with personnel, trucks, and equipment) were off-course, some as much as thousands of yards from their respective landing zone amongst the five beach areas (Utah, Omaha, Sword, Juno and Gold). The Americans in particular suffered heavy losses on Omaha beach due to the German fortifications being left intact. However by the end of the first day, most of the Allied objectives were accomplished even though the British and Canadian objective of capturing Caen proved too optimistic. The Germans launched no significant counterattack on the beaches as Hitler believed the landings to be a decoy. Only three days later the German High command realized that Normandy was the actual invasion, but by then the Allies had already consolidated their beachheads.

The bocage terrain of Normandy where the Americans had landed made it ideal ground for defensive warfare. Nevertheless, the Americans made steady progress and captured the deep-water port of Cherbourg on June 26, one of the primary objectives of the invasion. However, the Germans had mined the harbor and destroyed most of the port facilities before surrendering, and it would be another month before the port could be brought back into limited use. The British launched another attack on June 13 to capture Caen but were held back as the Germans had moved in large number of troops to hold the city. The city was to remain in German hands for another 6 weeks. It finally fell to British and Canadian forces on July 9.

Allied firepower, improved tactics, and numerical superiority eventually resulted in a breakout of American mechanized forces at the western end of the Normandy pocket in Operation Cobra on July 23. The allied advance to this point had been considerably slower than expected. Seven weeks after D-Day, U.S. First Army was holding an east-west line that ran from Caumont to Saint-Lô to Lessay on the Channel. Pre-D-Day projections had put the Americans on that line by D Plus Five [7] . When Hitler learned of the American breakout, he ordered his forces in Normandy to launch an immediate counter-offensive. However the German forces moving in open countryside were now easily targeted by Allied aircraft, as they had initially escaped Allied air attacks due to their well camouflaged defensive positions.

The Americans placed strong formations on their flanks which blunted the attack and then began to encircle the 7th Army and large parts of the 5th Panzer Army in the Falaise Pocket. Some 50,000 Germans were captured, but 100,000 managed to escape the pocket. Worse still, the British and Canadians—whose initial strategic objective to draw in enemy reserves and protect the American flanks so as to promote a later turning movement north had been achieved [8]—now began to break through the German lines. Any hope the Germans had of containing the Allied thrust into France by forming new defensive lines was now gone. The Allies raced across France, advancing as much as 600 miles in two weeks[9] The German forces retreated into Northern France, Holland and Belgium. By August 1944, Allied forces stationed in Corsica launched Operation Dragoon, invading the French Riviera on August 15 with the 6th Army Group, led by Lieutenant General Jacob Devers), and linked up with forces from Normandy. The clandestine French Resistance in Paris rose against the Germans on August 19, and the Free French 2nd Armored Division under General Philippe Leclerc, pressing forward from Normandy, received the surrender of the German forces on behalf of General von Choltiz from Paris and liberated the city on August 25.

Around this time the Germans began launching V-1's (known as the "buzz bomb"), the world's first cruise missile, at targets in southern England and Belgium. Later they would employ the much-larger V-2 rocket, a liquid-fuelled guided ballistic missile. These weapons were inaccurate and could only target large areas such as cities; they had little military effect and were intended to demoralize and/or terrorize Allied civilians.

Logistical problems plagued the Allies as they fanned out across France and the Low Countries, advancing towards the German border. With the supply lines still running back to Normandy, and critical shortages in fuel and other supplies all along the front, the Allies slowed the general advance and focused the available supplies on a narrow front strategy. Allied paratroopers and armor attempted a war-winning advance through the Netherlands and across the Rhine River with Operation Market Garden in September (the goal was to end the war by Christmas). The plan was to land paratroopers near bridges on the Rhine River, hold the position, and wait for the armour to cut through enemy lines to reinforce them and then cross into Germany. The plan was conceived and led by British General Montgomery, and included British, American, Polish, and Canadian forces. Although the plan encountered some initial success, many of the bridges were blown up, and the advancing armored columns ran into delays. As a result, the British 1st Airborne Division, holding the last bridge, was nearly annihilated. The Germans were able to entrench all along the front and the war continued through the winter.

In order to improve the supply situation, the Canadian First Army was assigned to clear the entrance to the port of Antwerp, the Scheldt estuary, which they successfully accomplished by late November 1944 making Canada the only country to successfully complete all D-Day objectives. In October, the Americans captured Aachen, the first major German city to be occupied.

Hitler had been planning to launch a major counteroffensive against the Allies since mid-September. The objective of the attack was to capture Antwerp. Not only would the capture or destruction of Antwerp prevent supplies from reaching the allied armies, it would also split allied forces in two, demoralizing the alliance and forcing its leaders to negotiate. For the attack, Hitler concentrated the best of his remaining forces, launching the attack through the Ardennes in southern Belgium, a hilly and in places a heavily wooded region, and the site of his victory in 1940. Dense cloud cover denied the Americans the use of their reconnaissance and ground attack aircraft.

Parts of the attack managed to break through the thinly-held American lines (about 4 divisions which were either new or refitting to cover about 70 miles of the front-line), and dash headlong for the Meuse. However the northern section of the line held, constricting the advance to a narrow corridor. The German advance was delayed at St. Vith, which American forces defended for several days. At the vital road junction of Bastogne, the American 101st Airborne Division and Combat Command B of the 10th Armoured Division held out, surrounded, for the duration of the battle. Patton's 3rd Army to the South made a rapid 90 degree turn and rammed into the German southern flank, relieving Bastogne.

The weather by this time had cleared unleashing allied air power as the German attack ground to a halt at Dinant. In an attempt to keep the offensive going, the Germans launched a massive air raid on Allied airfields in the Low Countries on January 1, 1945. The Germans destroyed 465 aircraft but lost 277 of their own planes. Whereas the Allies were able to make up their losses in days, the Luftwaffe was not capable of launching a major air attack again.[10]

Allied forces from the north and south met up at Houffalize and by the end of January they had pushed the Germans back to their starting positions. Many German units were caught in the pocket created by the Bulge and forced to surrender or retreat without their heavy equipment. Months of the Reich's war production were lost whereas German forces on the Eastern front were virtually starved of resources at the very moment the Red Army was preparing for its massive offensive against Germany. The final obstacle to the Allies was the river Rhine, which was crossed in late March 1945, aided by the fortuitous capture of the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen. Also, Operation Varsity, a parachute-assault in late March, got a foothold on the east bank of the Rhine River. Once the Allies had crossed the Rhine, the British fanned out northeast towards Hamburg, crossing the river Elbe and moving on towards Denmark and the Baltic Sea.

The U.S. 9th Army went south as the northern pincer of the Ruhr encirclement, and the U.S. 1st Army went north as the southern pincer of the Ruhr encirclement. These armies were commanded by General Omar Bradley who had over 1.3 million men under his command (the 12th Army Group). On April 4, the encirclement was completed, and the German Army Group B, which included the 5th Panzer Army, 7th Army and the 15th Army and was commanded by Field Marshal Walther Model, was trapped in the Ruhr Pocket. Some 300,000 German soldiers then became prisoners of war. The 1st and 9th U.S. Armies then turned east, halting their advance at the Elbe river where they met up with Soviet troops in mid-April.

Soviet-German War ("The Great Patriotic War")

The Eastern Front of the European Theatre of World War II encompassed the conflict in central and eastern Europe from June 22, 1941 to May 8, 1945. It was the largest theatre of war in history in terms of numbers of soldiers, equipment and casualties and was notorious for its unprecedented ferocity, destruction, and immense loss of life. The fighting involved millions of German and Soviet troops along a broad front hundreds of kilometres long. It was by far the deadliest single theatre of World War II, with over 5 million deaths on the Axis Forces; Soviet military deaths were about 10.6 million (out of which 2.8 - 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war (of 5.5 million) died in German captivity)[11][12][13]), and civilian deaths were about 14 to 17 million.[citation needed] More people fought and died on the Eastern Front than in all other theatres of World War II combined; the German army suffered 80% to 93% of all casualties there.[14][15] The fate of the Third Reich was decided at Stalingrad and sealed at Kursk.[citation needed] Although the Soviet Union was victorious in the war, the cost to the nation was an estimated 27 million dead, about half of all World War II casualties and the vast majority of allied deaths, and had devastated the Soviet economy in the struggle. In Soviet and Russian sources, the conflict is referred to as the Great Patriotic War.

Invasion of the Soviet Union

| “ | We have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down. | ” |

| — Adolf Hitler |

The battle of Greece and the invasion of Yugoslavia delayed the German invasion of the Soviet Union by a critical six weeks.

Three German Army Groups along with various other Axis military units who in total numbered over 4.3 million men, 3.3 million Germans and 1 million Axis, launched the invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Army Group North was deployed in East Prussia. Its main objectives were to secure the Baltic states and seize Leningrad. Opposite Army Group North were 2 Soviet Armies. The Germans threw their 600 tanks at the junction of the two Soviet Armies in that sector. The 4th Panzer Army's objective was to cross the River Neman and River Dvina which were the two largest obstacles in route to Leningrad. On the first day, the tanks crossed River Neman and penetrated 50 miles. Near Rasienai, the Panzers were counterattacked by 300 Soviet tanks. It took 4 days for the Germans to encircle and destroy the Soviet tanks. The Panzers then crossed River Dvina near Dvinsk, and approached Leningrad.

Army Group Center was deployed in Poland. Its main objective was to capture Moscow. Opposite Army Group Center were 4 Soviet Armies. Soviet forces occupied a salient which jutted into German territory with its center at Bialystok. Beyond, Bialystok was Minsk which was a key railway junction and guardian of the main highway to Moscow. 3rd Panzer Army punched through the junction of the two Soviet Armies from the North and crossed the River Neman, and 2nd Panzer Army crossed the River Bug from the south. While the Panzers attacked, the Infantry armies struck at the Salient and encircled Soviet troops at Bialystok. The Panzer Armies' objective was to meet at Minsk and prevent any Soviet withdrawal. On June 27, 2nd and 3rd Panzer Armies met up at Minsk advancing 200 miles into Soviet Territory. In the vast pocket between Minsk and the Polish border, 32 Soviet Infantry and 8 Tank Divisions were encircled and were mercilessly attacked. Soviet soldiers numbering 290,000 were captured, while another 250,000 managed to escape.

Army Group South was deployed in Southern Poland and Romania and also included two Romanian Armies and several Italian, Slovakian and Hungarian Divisions. Its objective was to secure the oil fields of the Caucasus. In the South, Soviet commanders quickly reacted to the German attack and commanded tank forces vastly outnumbering the Germans. Opposite the Germans in the South were 3 Soviet Armies. The German struck at the junctions of the 3 Soviet Armies but 1st Panzer Army struck right through the Soviet Army with the objective of capturing Brody. On June 26, five Soviet Mechanized Corps with over 1,000 Tanks mounted a massive counterattack on 1st Panzer Army. The Battle was among the fiercest of the invasion lasting over 4 days. In the end the Germans prevailed but the Soviets inflicted heavy losses on the 1st Panzer Army. With the failure of the Soviet Armored offensive, the last substantial Soviet tank forces in the south were now spent.

On July 3, Hitler finally gave the go-ahead for the Panzers to resume their drive east after the infantry armies had caught up. The next objective of Army Group Center was the city of Smolensk which commanded the road to Moscow. Facing the Germans was an old Russian defensive line where the Soviets had deployed 6 Armies. On July 6, the Soviets launched an attack with 700 Tanks against the 3rd Panzer Army. The Germans, using their overwhelming air superiority, wiped out the Soviet tanks. The 2nd Panzer Army crossed the River Dneiper and closed on Smolensk from the south while 3rd Panzer Army after defeating the Soviet counter attack approached Smolensk from the north. Trapped between their pincers were 3 Soviet Armies. On July 26, the Panzers closed the gap and then began to eliminate the pocket which yielded over 300,000 Soviet prisoners but 200,000 evaded capture. Hitler by now had lost faith in battles of encirclement and wanted to defeat the Soviets by inflicting severe economic damage which meant seizing the oil fields in the south and Leningrad in the North. Tanks from Army Group Center were diverted to Army Group North and South to aid them. Hitler's generals vehemently opposed this as Moscow was only 200 miles away from Army Group Center and the bulk of the Red Army was deployed in that sector and only an attack there could hope to end the war quickly. But Hitler was adamant and the Tanks from Army Group Center arrived and reinforced the 4th Panzer Army in the north which subsequently broke through the Soviet defenses on August 8 and by the end of August was only 30 miles from Leningrad. Meanwhile the Finns had pushed South East on both sides of Lake Ladoga reaching the old Finnish Soviet frontier.

In the South by mid-July below the Pinsk Marshes, the Germans had gotten to within a few miles of Kiev. The 1st Panzer Army then went South while the German 17th Army which was on 1st Panzer Army's southern flank struck east and between them trapped 3 Soviet Armies near Uman. As the Germans eliminated the pocket, their tanks turned north and crossed the Dneiper. Meanwhile 2nd Panzer Army, which was diverted from Army Group Center on Hitler's orders, had crossed the River Desna with 2nd Army on its right flank. This move resulted in the trapping of 4 Soviet Armies and parts of two others. The encirclement of Soviet forces in Kiev was achieved on September 16. The encircled Soviets did not give up easily, a savage battle now ensued lasting for 10 days, after which the Germans claimed over 600,000 Soviet soldiers captured. Hitler called it the greatest battle in history. After Kiev, the Red Army no longer outnumbered the Germans and there were no more reserves. To defend Moscow, Stalin had only 800,000 men left.

The Red Army was outflanked and on September 8 1941 the Germans had fully encircled Leningrad and Hitler ordered Leningrad to be besieged. The siege lasted for a total of 900 days, from September 8 1941 until January 27 1944. The city's almost 3 million civilians (including about 400,000 children) refused to surrender and endured rapidly increasing hardships in the encircled city.[16] Food and fuel stocks were limited to a mere 1-2 month supply, public transport was not operational and by the winter of 1941-42 there was no heating, no water supply, almost no electricity and very little food.[16] In January 1942 in the depths of an unusually cold winter, the city's food rations reached an all time low of only 125 grams (about 1/4 of a pound) of bread per person per day.[16] In just two months, January and February of 1942, 200,000 people died in Leningrad of cold and starvation.[16] Despite these tragic losses and the inhuman conditions the city's war industries still continued to work and the city did not surrender.

The Soviets had mounted an increasing number of attacks against Army Group Center but lacking tanks it was in no position to go on the offensive. Hitler had changed his mind and decided that tanks be sent back to Army Group Center for its all out drive on Moscow. Operation Typhoon, the drive on Moscow began on October 2. In front of Army Group Center was a series of elaborate defense lines. The Germans easily penetrated the first line as 2nd Panzer Army, returning from the south, took Orel which was 75 miles behind the Soviet first defense line. The Germans then pushed in and the vast pocket yielded 663,000 Soviet prisoners. Soviet forces now had only 90,000 men and 150 tanks left for the defense for Moscow.

Almost from the beginning of Operation Typhoon the weather had deteriorated steadily, slowing the German advance on Moscow to as little as 2 miles a day. On October 31, the Germany Army High Command ordered a halt on Operation Typhoon as the armies were re-organized. The pause gave the Soviets time to build up new armies and bring in the Soviet troops from the east as the neutrality pact signed by the Soviets and Japanese in April, 1941 assured Stalin that there was no longer a threat from the Japanese.

On November 15, the Germans resumed the attack on Moscow. Facing the Germans were 6 Soviet Armies. The Germans intended to let the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies cross the Moscow Canal and envelop Moscow from the North East. The 2nd Panzer Army would attack Tula and then close in on Moscow from the South and the 4th Army would smash in the center. However, on November 22, Soviet Siberian Troops were unleashed on the 2nd Panzer Army in the South which inflicted a shocking defeat on the Germans. The 4th Panzer Army succeeded in crossing the Moscow canal and on December 2 had penetrated to within 15 miles of the Kremlin. But by then the first blizzards of the winter began and the Wehrmacht was not equipped for winter warfare. Frostbite and disease had caused more casualties than combat; dead and wounded had already reached 155,000 in 3 weeks. Some divisions were now at 50% strength and the bitter cold had caused severe problems for guns and equipment. Weather conditions grounded the Luftwaffe. Hitler's plans miscarried before the onset of severe winter weather; he was so confident of a lightning victory that he did not prepare for even the possibility of winter warfare in the Soviet Union. Yet his eastern army suffered more than 734,000 casualties (about 23 percent of its average strength of 3,200,000 troops) during the first five months of the invasion, and on 27 November 1941, General Eduard Wagner, the Quartermaster General of the German Army, reported that "We are at the end of our resources in both personnel and materiel. We are about to be confronted with the dangers of deep winter." Newly built up Soviet troops near Moscow now numbered over 500,000 men and Zhukov on December 5 launched a massive counter attack which pushed the Germans back over 200 miles but no decisive breakthrough was achieved. The invasion of the Soviet Union had so far cost the Germans over 250,000 dead, 500,000 wounded and most of their tanks.

German attack stalls

On January 6, 1942, Stalin, confident of his earlier victory, ordered a general counter-offensive. Initially the attacks made good ground as Soviet pincers closed around Demyansk and Vyazma and threatening attacks were made towards Smolensk and Bryansk. But despite these successes the Soviet offensive soon ran out of steam. By March, the Germans had recovered and stabilized their line and secured the neck of the Vyazma Pocket. Only at Demyansk was there any serious prospect of a major Soviet victory. Here a large part of the German 16th Army had been surrounded. Hitler ordered no withdrawal and the 92,000 men trapped in the pocket were to hold their ground while they were re-supplied by air. For 10 weeks they held out until April when a land corridor was opened to the west. The German forces retained Demyansk until they were permitted to withdraw in February 1943.

In May, the Soviets attempted to retake the city of Kharkov, in Eastern Ukraine. They opened with concentric attacks on either side of Kharkov and in both sides broke through German lines and a serious threat to the city emerged. In response, the Germans accelerated the plans for their own offensive and launched it 5 days later. The German 6th Army struck at the salient from the south and encircled the entire Soviet army assaulting Kharkov. In the last days of May, the Germans destroyed the forces inside the pocket. Of the Soviet troops inside the pocket, 70,000 were killed, 200,000 captured and only 22,000 managed to escape.

Hitler had by now realized that his Armies were too weak to carry out an offensive on all sectors of the Eastern Front, but if the Germans could seize the oil and fertile rich area of the Southern Soviet Union this would give the Germans the means to continue with the war. Operation Blue attempted the destruction of the Red Army's southern front, consolidation of the Ukraine west of the River Volga, and the capture of the Caucaus oil fields. The Germans reinforced Army Group South by transferring divisions from other sectors and getting divisions from Axis allies. By late June, Hitler had 74 Divisions ready to go on the offensive, 51 of them German.[citation needed]

The Soviets did not know where the main German offensive of 1942 would come. Stalin was convinced that the German objective of 1942 would be Moscow and over 50% of all Red Army troops were deployed in the Moscow region. Only 10% of Soviet troops were deployed in the Southern Soviet Union.[citation needed]

On June 28, 1942, the German offensive began. Everywhere Soviet forces fell back as the Germans sliced through Soviet defenses. By July 5, forward elements of 4th Panzer Army reached the River Don near Voronezh and got embroiled in a bitter battle to capture the city. The Soviets, by tying down 4th Panzer Army, gained vital time to reinforce their defenses. The Soviets for the first time in the war were not fighting to hold hopelessly exposed positions but were retreating in good order. As German pincers closed in they only found stragglers and rear guards. Angered by the delays, Hitler re-organized Army Group South to two smaller Army Groups, Army Group A and Army Group B. The bulk of the Armored forces were concentrated with Army Group A which was ordered to attack towards the Caucasus oil fields while Army Group B was ordered to capture Stalingrad and guard against any Soviet counter attacks.

By July 23, the German 6th Army had taken Rostov but Soviet troops fought a skillful rearguard action which embroiled the Germans in heavy urban fighting to take the city. This also allowed the main Soviet formations to escape encirclements. With the River Don's crossing secured in the south and with the 6th Army's advance flagging, Hitler sent the 4th Panzer Army back to join up with 6th Army. In late July, 6th Army resumed its offensive and by August 10, 6th Army cleared the Soviet presence from the west bank of the River Don but Soviet troops held out in some areas, further delaying 6th Army's march east. In contrast, Army Group A after crossing the River Don on July 25 had fanned out on a broad front. The German 17th Army swung west towards the Black Sea, while the 1st Panzer Army attacked towards the south and east sweeping through country largely abandoned by Soviet troops. On August 9, 1st Panzer Army reached the foothills of the Caucasus mountains, an advance of more than 300 miles.

In order to protect their forces in the Caucasus, the Germans attempted to capture Stalingrad, on their northeastern flank, crossing the Don River and advancing on the city. Germans bombers killed over 40,000 people and turned much of the city into rubble. The Soviet leadership realized that the German plan was the seizure of the oil fields and began sending large number of troops from the Moscow sector to reinforce their troops in the South. Zhukov, one of Stalin's most trusted generals, assumed command of the Stalingrad front in early September and mounted a series of attacks from the North which further delayed the German 6th Army's attempt to seize Stalingrad. On September 13, the Germans advanced through the southern suburbs and by September 23, 1942, the main factory complex was surrounded and the German artillery was within range of the quays on the river, across which the Soviets evacuated wounded and brought in reinforcements. Ferocious street fighting, hand-to-hand conflict of the most savage kind, now ensued in the ruins of the city. Exhaustion and deprivation gradually sapped men's strength. Hitler, who had become obsessed with the battle of Stalingrad, refused to countenance a withdrawal. General Paulus, in desperation, launched yet another attack early in November by which time the Germans had managed to capture 90% of the city. The Soviets, however, had been building up massive forces on the flanks of Stalingrad which were by this time severely undermanned as the bulk of the German forces had been concentrated in capturing the city and Axis satellite troops were left guarding the flanks. The Soviets launched Operation Uranus on November 19 1942, with twin attacks that met at the city of Kalach four days later, encircling the 6th Army in Stalingrad.

The Germans requested permission to attempt a breakout, which was refused by Hitler, who ordered Sixth Army to remain in Stalingrad where he promised they would be supplied by air until rescued. About the same time, the Soviets launched Operation Mars in a salient near the vicinity of Moscow. Its objective was to tie down Army Group Center and to prevent it from reinforcing Army Group South at Stalingrad.

Meanwhile, Army Group A's advance into the Caucasus had stalled as Soviet troops had destroyed the oil production facilities and a year's work was required to bring them back up, the other remaining oil fields lay south of the Caucasus Mountains. Throughout August and September, German Mountain troops probed for a way through but by October, with the onset of winter, they were no closer to their objective. With German troops encircled in Stalingrad, and Soviet armies threatening their lines of retreat, Army Group A began to fall back.

By December, Field Marshal von Manstein hastily put together a German relief force of units composed from Army Group A to relieve the trapped Sixth Army. Unable to get reinforcements from Army Group Center, the relief force only managed to get within 50 kilometers (30 mi) before they were turned back by the Soviets. By the end of the year, the Sixth Army was in desperate condition, as the Luftwaffe was able to supply only about a sixth of the supplies needed.

Shortly before surrendering to the Red Army on February 2, 1943, Friedrich Paulus was promoted to Field Marshal. This was a message from Hitler, because no German Field Marshal had ever surrendered his troops or been taken alive. Of the 300,000 strong 6th Army, only 91,000 survived to be taken prisoner, including 22 generals, of which only 5,000 men ever returned to Germany after the war. This was to be the greatest, and most costly, battle in terms of human life in history. Around 2 million men were killed or wounded on both sides, including civilians, with Axis casualties estimated to be approximately 850,000 and 750,000 for the Soviets.

Germany's second push

| “ | They want a war of annihilation. We will give them a war of annihilation. | ” |

After the surrender of the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad on February 2, 1943, the Red Army launched eight offensives during the winter. Many were concentrated along the Don basin near Stalingrad. These attacks resulted in initial gains until German forces were able to take advantage of the over extended and weakened condition of the Red Army and launch a counter attack to re-capture the city of Kharkov and surrounding areas. This was to be the last major strategic German victory of World War II.

The rains of spring inhibited campaigning in the Soviet Union, but both sides used the interval to build up for the inevitable battle that would come in the summer. The start date for the offensive had been moved repeatedly as delays in preparation had forced the Germans to postpone the attack. By July 4, the Wehrmacht, after assembling their greatest concentration of firepower during the whole of World War II, launched their offensive against the Soviet Union at the Kursk salient. Their intentions were known by the Soviets, who hastened to defend the salient with an enormous system of earthwork defenses. The Germans attacked from both the north and south of the salient and hoped to meet in the middle, cutting off the salient and trapping 60 Soviet divisions. The German offensive in the Northern sector was ground down as little progress was made through the Soviet defenses but in the Southern Sector there was a danger of a German breakthrough. The Soviets then brought up their reserves to contain the German thrust in the Southern sector, and the ensuing Battle of Kursk became the largest tank battle of the war, near the city of Prokhorovka. The Germans lacking any sizable reserves had exhausted their armored forces and could not stop the Soviet counteroffensive that threw them back across their starting positions.

The Soviets captured Kharkov following their victory at Kursk and with the Autumn rains threatening, Hitler agreed to a general withdrawal to the Dnieper line in August. As September proceeded into October, the Germans found the Dnieper line impossible to hold as the Soviet bridgeheads grew. Important Dnieper towns started to fall, with Zaporozhye the first to go, followed by Dnepropetrovsk. Early in November the Soviets broke out of their bridgeheads on either side of Kiev and recaptured the Ukrainian capital. The 1st Ukrainian Front attacked at Korosten on Christmas Eve, and the Soviet advance continued along the railway line until the 1939 Soviet-Polish border was reached.

Soviet counter-attack and conquest of Germany

The Soviets launched their winter offensive in January 1944 in the Northern sector and relieved the brutal siege of Leningrad. The Germans conducted an orderly retreat from the Leningrad area to a shorter line based on the lakes to the south. By March the Soviets struck into Romania from Ukraine. The Soviet forces encircled the First Panzer Army north of the Dniestr river. The Germans escaped the pocket in April, saving most of their men but losing their heavy equipment. During April, the Red Army launched a series of attacks near the city of Iaşi, Romania, aimed at capturing the strategically important sector which they hoped to use as a springboard into Romania for a summer offensive. The Soviets were held back by the German and Romanian forces when they launched the attack through the forest of Târgul Frumos as Axis forces successfully defended the sector through the month of April.

As Soviet troops neared Hungary, German troops occupied Hungary on March 20. Hitler thought that Hungarian leader Admiral Miklós Horthy might no longer be a reliable ally. Germany's other Axis ally, Finland had sought a separate peace with Stalin in February 1944, but would not accept the initial terms offered. On June 9, the Soviet Union began the Fourth strategic offensive on the Karelian Isthmus that, after three months, forced Finland to accept an armistice.

Before the Soviets could begin their Summer offensive into Belarus they had to clear the Crimea peninsula of Axis forces. Remnants of the German Seventeenth Army of Army Group South and some Romanian forces were cut off and left behind in the peninsula when the Germans retreated from the Ukraine. In early May, the Red Army's 3rd Ukrainian Front attacked the Germans and the ensuing battle was a complete victory of the Soviet forces and a botched evacuation effort across the Black Sea by Germany failed.

With the Crimea cleared, the long awaited Soviet summer offensive codenamed, Operation Bagration, began on June 22, 1944 which involved 2.5 million men and 6,000 tanks. Its objective was to clear German troops from Belarus and crush German Army Group Center which was defending that sector. The offensive was timed to coincide with the Allied landings in Normandy but delays caused the offensive to be postponed for a few weeks. The subsequent battle resulted in the destruction of German Army Group Centre and over 800,000 German casualties, the greatest defeat for the Wehrmacht during the war. The Soviets swept forward, reaching the outskirts of Warsaw on July 31.

The proximity of the Red Army led the Poles in Warsaw to believe they would soon be liberated. On August 1, they revolted as part of the wider Operation Tempest. Nearly 40,000 Polish resistance fighters seized control of the city. The Soviets, however, did not advance any further.[17] The only assistance given to the Poles was artillery fire, as German army units moved into the city to put down the revolt. The resistance ended on October 2. German units then destroyed most of what was left of the city.

In Yugoslavia, the tide of the civil war was turning to favor the Partisans. On 16 June 1944, the Treaty of Vis was signed between the Partisans and the Royal Government, officially making the Partisans the regular army of Yugoslavia. By the end of August, Josip Tito was appointed as the Chief-of-Staff of the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland, although his Royalist rival Mihajlović and many Chetniks continued fighting their own resistance until their final defeat in the Battle on Lijevča field by a Croatian coalition.

Following the destruction of German Army Group Center, the Soviets attacked German forces in the south in mid-July 1944, and in a month's time they cleared Ukraine of German presence inflicting heavy losses on the Germans. Once Ukraine had been cleared the Soviet forces struck into Romania. The Red Army's 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts engaged German Heeresgruppe Südukraine, which consisted of German and Romanian formations, in an operation to occupy Romania and destroy the German formations in the sector. The result of the Battle of Romania was a complete victory for the Red Army, and a switch of Romania from the Axis to the Allied camp. Bulgaria surrendered to the Red Army in September. Following the German retreat from Romania, the Soviets entered Hungary in October 1944 but the German Sixth Army encircled and destroyed three corps of Marshal Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky's Group Pliyev near Debrecen, Hungary. The rapid assault the Soviets had hoped that would lead to the capture of Budapest was now halted and Hungary would remain Germany's ally until the end of the war in Europe. This battle would be the last German victory in the Eastern Front.

As the Red Army continued their advance into the Balkans, Bulgaria left the Axis on September 9, and German troops abandoned Greece on October 12. Concurrently, Yugoslav Partisans shifted operations into Serbia, freed Belgrade on October 20 with Soviet help, and assisted the Albanian Resistance rout the Germans by November 29. By year end, the Partisans controlled the eastern half of Yugoslavia and the Dalmatian coast, and were ready for a final westward offensive by late March, 1945.

The Soviets recovered from their defeat in Debrecen and advancing columns of the Red Army liberated Belgrade in late December and reached Budapest on December 29, 1944 and en-circled the city where over 188,000 Axis troops were trapped including many German Waffen-SS. The Germans held out till February 13, 1945 and the siege became one of the bloodiest of the war. Meanwhile the Red Army's 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Baltic Fronts engaged the remnants of German Army Group Center and Army Group North to capture the Baltic region from the Germans in October 1944. The result of the series of battles was a permanent loss of contact between Army Groups North and Centre, and the creation of the Courland Pocket in Latvia where the 18th and 16th German Armies, numbering over 250,000 men were trapped and would remain there till the end of the war.

With the Balkans and most of Hungary cleared of German troops by late December 1944, the Soviets began a massive re-deployment of their forces to Poland for their upcoming Winter offensive. Soviet preparations were still on-going when Churchill asked Stalin to launch his offensive as soon as possible to ease German pressure in the West. Stalin agreed and the offensive was set for January 12, 1945. Konev’s armies attacked the Germans in southern Poland and expanded out from their Vistula River bridgehead near Sandomierz. On January 14, Rokossovskiy’s armies attacked from the Narew River north of Warsaw. Zhukov's armies in the center attacked from their bridgeheads near Warsaw. The combined Soviet offensive broke the defenses covering East Prussia, leaving the German front in chaos.

Zhukov took Warsaw by January 17 and by January 19, his tanks took Łódź. That same day, Konev's forces reached the German prewar border. At the end of the first week of the offensive, the Soviets had penetrated 160 kilometers (100 mi) deep on a front that was 650 kilometers (400 mi) wide. The Soviet onslaught finally halted on the Oder River at the end of January, only 60 kilometers (40 mi) from Berlin.

The Soviets had hoped to capture Berlin by mid-February but that proved hopelessly optimistic. German resistance which had all but collapsed during the initial phase of the attack had stiffened immeasurably. Soviet supply lines were over-extended. The spring thaw, the lack of air support, and fear of encirclement through flank attacks from East Prussia, Pommern and Silesia led to a general halt in the Soviet offensive. The newly created Army Group Vistula, under the command of Heinrich Himmler, attempted a counter-attack on the exposed flank of the Soviet Army but failed by February 24. This made it clear to Zhukov that the flank had to be secure before any attack on Berlin could be mounted. The Soviets then re-organized their forces and then struck north and cleared Pomerania and then attacked the south and cleared Silesia of German troops. In the south, three German attempts to relieve the encircled Budapest garrison failed, and the city fell to the Soviets on February 13. Again the Germans counter-attacked; Hitler insisting on the impossible task of regaining the Danube River. By March 16, the attack had failed, and the Red Army counter-attacked the same day. On March 30, they entered Austria and captured Vienna on April 13.

Hitler had believed that the main Soviet target for their upcoming offensive would be in the south near Prague and not Berlin and had sent the last remaining German reserves to defend that sector. The Red Army's main goal was in fact Berlin and by April 16 it was ready to begin its final assault on Berlin. Zhukov's forces struck from the center and crossed the Oder river but got bogged down under stiff German resistance around Seelow Heights. After three days of very heavy fighting and 33,000 Soviet soldiers dead,[18] the last defenses of Berlin were breached. Konev crossed the Oder river from the South and was within striking distance of Berlin but Stalin ordered Konev to guard the flanks of Zhukov's forces and not attack Berlin, as Stalin had promised the capture of Berlin to Zhukov[citation needed]. Rokossovskiy’s forces crossed the Oder from the North and linked up with British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's forces in northern Germany while the forces of Zhukov and Konev captured Berlin.

By April 24, the Soviet army groups had encircled the German Ninth Army and part of the 4th Panzer Army. These were main forces that were supposed to defend Berlin but Hitler had issued orders for these forces to hold their ground and not retreat. Thus the main German forces which were supposed to defend Berlin were trapped southeast of the city. Berlin was encircled around the same time and as a final resistance effort, Hitler called for civilians, including teenagers and the elderly, to fight in the Volkssturm militia against the oncoming Red Army. Those marginal forces were augmented by the battered German remnants that had fought the Soviets in Seelow Heights. Hitler ordered the encircled Ninth Army under General Theodor Busse to break out and link up with the German Twelfth Army under General Walther Wenck. After linking up, the armies were to relieve Berlin, an impossible task. The surviving units of the Ninth Army were instead driven into the forests around Berlin near the village of Halbe where they were involved in particularly fierce fighting trying to break through the Soviet lines and reach the Twelfth Army. A minority managed to join with the Twelfth Army and fight their way west to surrender to the Americans. Meanwhile the fierce urban fighting continued in Berlin. The Germans had stockpiled a very large quantity of panzerfausts and took a very heavy toll on Soviet tanks in the rubble filled streets of Berlin. However, the Soviets employed the lessons they learned during the urban fighting of Stalingrad and were slowly advancing to the center of the city. German forces in the city resisted tenaciously, in particular the SS Nordland which was made of foreign SS volunteers, because they were ideologically motivated and they believed that they would not live if captured. The fighting was house-to-house and hand-to-hand. The Soviets sustained 360,000 casualties; the Germans sustained 450,000 including civilians and above that 170,000 captured. Hitler and his staff moved into the Führerbunker, a concrete bunker beneath the Chancellery, where on April 30, 1945, he committed suicide, along with his bride, Eva Braun.

End of the war in Europe

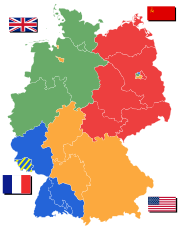

Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin made arrangements for post-war Europe at the Yalta Conference in February 1945. Their meeting resulted in many important resolutions such as the formation of the United Nations, democratic elections in Poland, borders of Poland moved westwards at the expense of Germany, Soviet nationals were to be repatriated and it was agreed that Soviet Union would attack Japan within three months of Germany's surrender.

After Hitler's death (on April 30), Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz became leader of the German government but the German war effort quickly disintegrated. German forces in Berlin surrendered the city to Soviet troops on May 2, 1945. The German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, 1945, at General Alexander's headquarters, and German forces in northern Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands surrendered on May 4. The German High Command under Generaloberst Alfred Jodl surrendered unconditionally all remaining German forces on May 7 in Rheims, France. The western Allies celebrated "V-E Day" on May 8, since the final German surrender was signed in Berlin on that day. The Soviet Union celebrated "Victory Day" on May 9 due to time zone differences; the final cessation of German military activity happened at one minute past midnight by their clock. Some remnants of German Army Group Center continued resistance until May 11 or May 12 (see Prague Offensive).[19]

Asia-Pacific Theatre

Events leading up to the war in Asia

After World War I, the victorious Western powers adopted policies that recognized Japan as a colonial power. Many Japanese politicians and militarist leaders, such as Fumimaro Konoe and Sadao Araki, promoted the idea that Japan had a right to conquer Asia and unify it, under the rule of Emperor Hirohito.

Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 and China in 1937 to bolster its meager stock of natural resources, to relieve Japan from population pressures and to extend its colonial realm to a wider area. The Japanese made initial advances but were stalled in the Battle of Shanghai. The city eventually fell to the Japanese in December 1937, with the capital city Nanjing. As a result, the Chinese Nationalist government moved its seat to Wuhan and then to Chongqing for the remainder of the war. Conquered areas of China became subject to a harsh occupation, with many atrocities against civilians, most notably the Rape of Nanking. The Japanese Army also frequently used chemical weapons. Neither Japan or China officially declared war, for a similar reason—fearing declaration of war would alienate Europe and the United States, who might then cut off supplies badly needed to continue their war efforts.

In Spring 1939, Soviet and Japanese forces clashed in Mongolia. The growing Japanese presence in the Far East was seen as a major strategic threat by the Soviet Union, and Soviet fear of having to fight a two front war was a primary reason for the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the Nazis (other historians mention the Munich Agreement as a supposition to this pact). The Japanese invasion of Mongolia was repulsed by Soviet units under General Georgiy Zhukov. Following this battle, the Soviet Union and Japan were at peace until 1945. Japan looked south to expand its empire, leading to conflict with the United States over the Philippines and control of shipping lanes to the Dutch East Indies. The Soviet Union and Japan eventually signed a non-agression pact in 1941. The Soviet Union focused on the west, with their eastern flank secured, while the Japanese directed their attention south, towards the British, Dutch, and American colonies of the South Pacific.

Japanese forces invaded French Indochina on September 22, 1940. The United States (after having renounced the U.S.-Japanese trade treaty of 1911), United Kingdom, Australia and the Netherlands (which controlled the oil of the Dutch East Indies), reacted in 1941 by instituting embargoes on exports of natural resources to Japan. The western powers also began making loans to China and providing covert military assistance.

Japan was faced with the choice of withdrawing from China and Indochina, negotiating some compromise, buying what they needed somewhere else, or going to war to conquer territories that contained oil, iron ore, bauxite and other resources necessary for continued operations in China. Japan's leaders believed that the existing Allies were preoccupied with the war against Germany, and that the United States would not be war-ready for years and would compromise before waging full-scale war. Japan thus proceeded with its plans for the war in the Pacific by launching nearly simultaneous attacks on Malaya, Thailand, Hong Kong, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Wake Island.

For propaganda purposes, Japan's leaders stated that the goal of its military campaigns was to create the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. This, they claimed, would be a co-operative league of Asian nations, freed by Japan from European imperialist domination, and liberated to achieve autonomy and self-determination. In practice, occupied countries and peoples were completely subordinate to Japanese authority.

China

| “ | I praise the Army for cutting down like weeds large numbers of the enemy. | ” |

| — Hirohito |

The Chinese Nationalist Army, under Chiang Kai-shek, and the Communist Chinese Army, under Mao Zedong, had been fighting a civil war since 1927, but agreed to a truce to fight the invading Japanese. Mao's forces were incorporated into the New Fourth Army and the Eighth Route Army, subordinate units within the Nationalist Army. Following the New Fourth Army Incident, the cooperation between the KMT and CCP fell apart. Conflict between Nationalist and Communist forces emerged long before the war; it continued after and, to an extent, even during the war, though less openly.

On December 3, 1941, the Imperial General Headquarters authorized general Yasuji Okamura to implement the sanko sakusen in North China [20].